Section 1 - The Problem

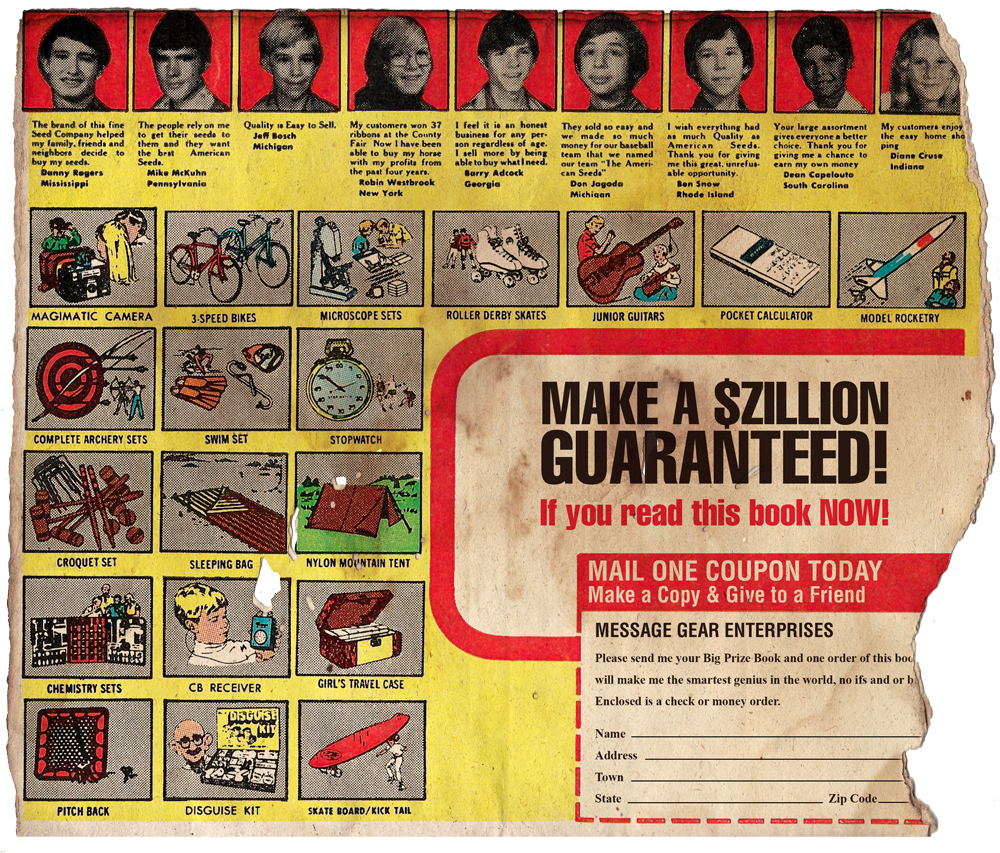

In the 1940s and 1970s, comic book pages were packed with mini daydreams of metamorphosis, self-assurance, and validation. A child could purchase hero biceps, breed "Sea-Monkeys" in a fishbowl, or see "X-Ray Specs" that purportedly saw through to the hidden for a few dollars. These ads, though lighthearted in appearance, were an early and potent type of psychological advertising—one that abolished the difference between fantasy and exploitation.

At the heart of this movement was one premise: desire could be manufactured. Every ad constructed a narrative of deficiency followed by a magical solution. The weakling boy is now the "He-Man." The isolating child is now a monarch of little people. The curious mind now has forbidden sight. Advertisers hawked not tangible commodities but symbols of identity and empowerment with exaggerated copy and sensational imagery.

These messages socialized youth following the war to understand success, masculinity, and self-worth in other ways. They expressed the wider culture's belief in progress and consumerism, that personal change could be ordered in the mail. While the merchandise never fulfilled the marketing hype, the emotional power was maintained—the ability to generate need, fantasy, and eventually, belief, across generations.

Now, the comic-book ads themselves are early examples of hyperreality, wherein the representation outstrips the power of truth itself. We can spot the early beginnings of the same cluster of sales methods applied today to digital and social media: instant fixes, aspirational imagery, and reward of feeling. Knowing this history, we can not only ask ourselves how we were sold the impossible once—but how we are still sold it.

Section 2 - Research & Findings

Unpacking Persuasion with Semiotics and Media Theory

To understand how these comic book advertisements impacted perception, this research examined them through two theoretical models — Roland Barthes' semiotic theory and Marshall McLuhan's media theory. Together, they reveal to us not just what these ads communicated, but how their medium amplified the message.

Barthes: Reading the Myth

Barthes viewed advertising as a new mythology — a system of signs that turns products into signs of meaning. In the advertisements in comic books, everything was a sign: the muscled superhero, the bold lettering, the "before-and-after" change. On one concrete level, they sold inexpensive baubles; on another cultural level, they sold ideals of power, masculinity, and membership. By denotation and connotation, the ads turned routine drawings into emotional commitments. Barthes' reading discloses the way the photos became myths of transformation, teaching young readers to identify consumption with self.

McLuhan: The Medium as the Message

The media theory of McLuhan extends this analysis further by illustrating the comic book itself as being a component of the persuasion. The medium united storytelling and advertising in the same visual rhythm — i.e., the reader consumed heroism and consumerism simultaneously. Stationed alongside heroic stories, the ads appropriated the legitimacy of the comic world: that anyone can be something more than ordinary. In doing so, the medium legitimized belief, turning the act of reading into an act of wanting and dreaming.

Cultural and Psychological Findings

Archival information and visual analysis discovered that these ads thrived in a period of post-war optimism and growing consumer confidence. They captured society's obsession with progress, technology, and self-improvement. Every ad became a distillation of the American Dream condensed into a single panel — speedy results, easy success, boundless possibility. What began as entertainment eventually turned into a model for craving, altering the manner by which later generations would respond to visual temptation on television, in film, and on the internet.

Section 3 - From Research to Visual Reinvention

The project began with a question: How might the language of vintage comic book advertising be reinterpreted to unleash its persuasive power?

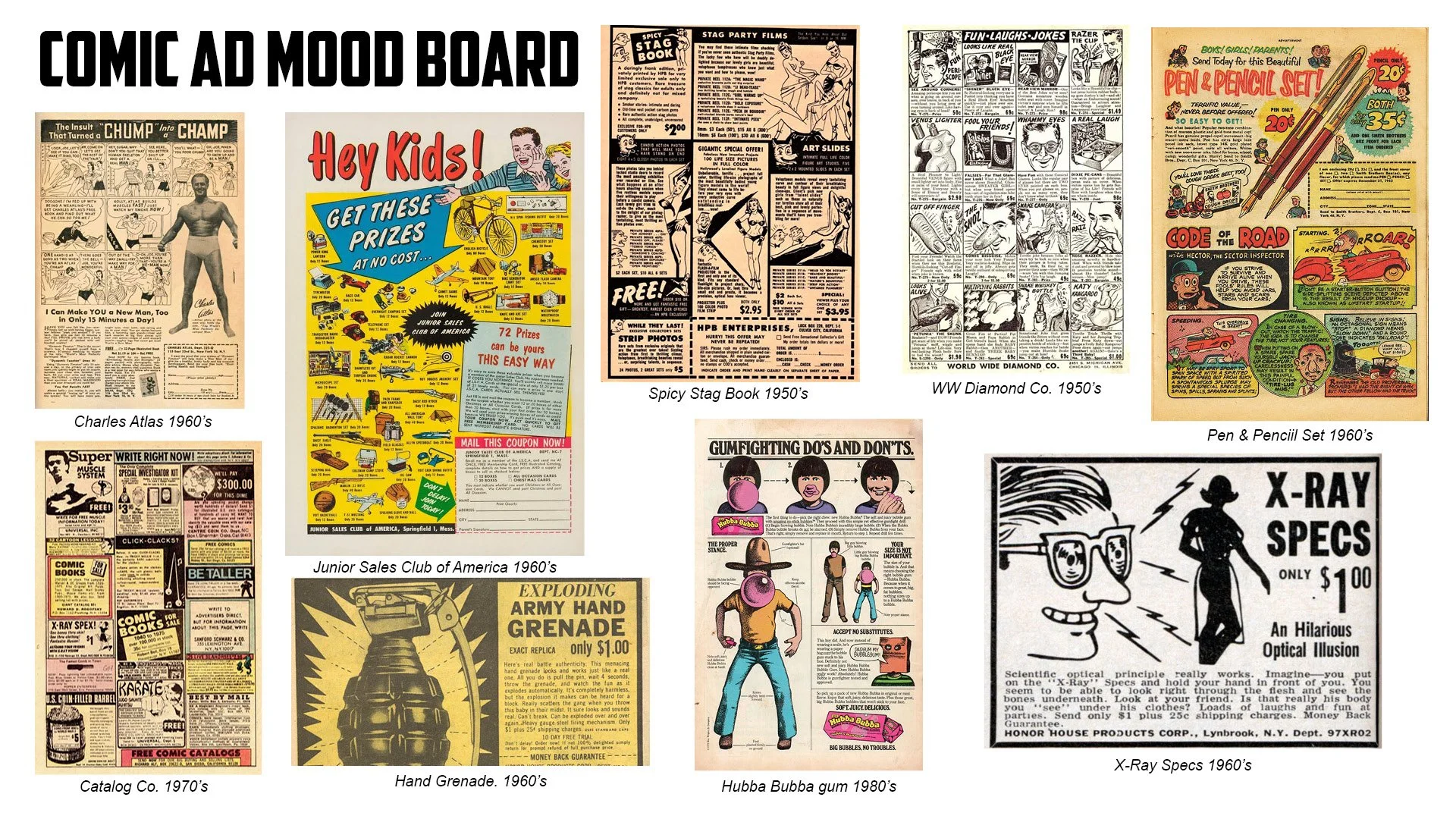

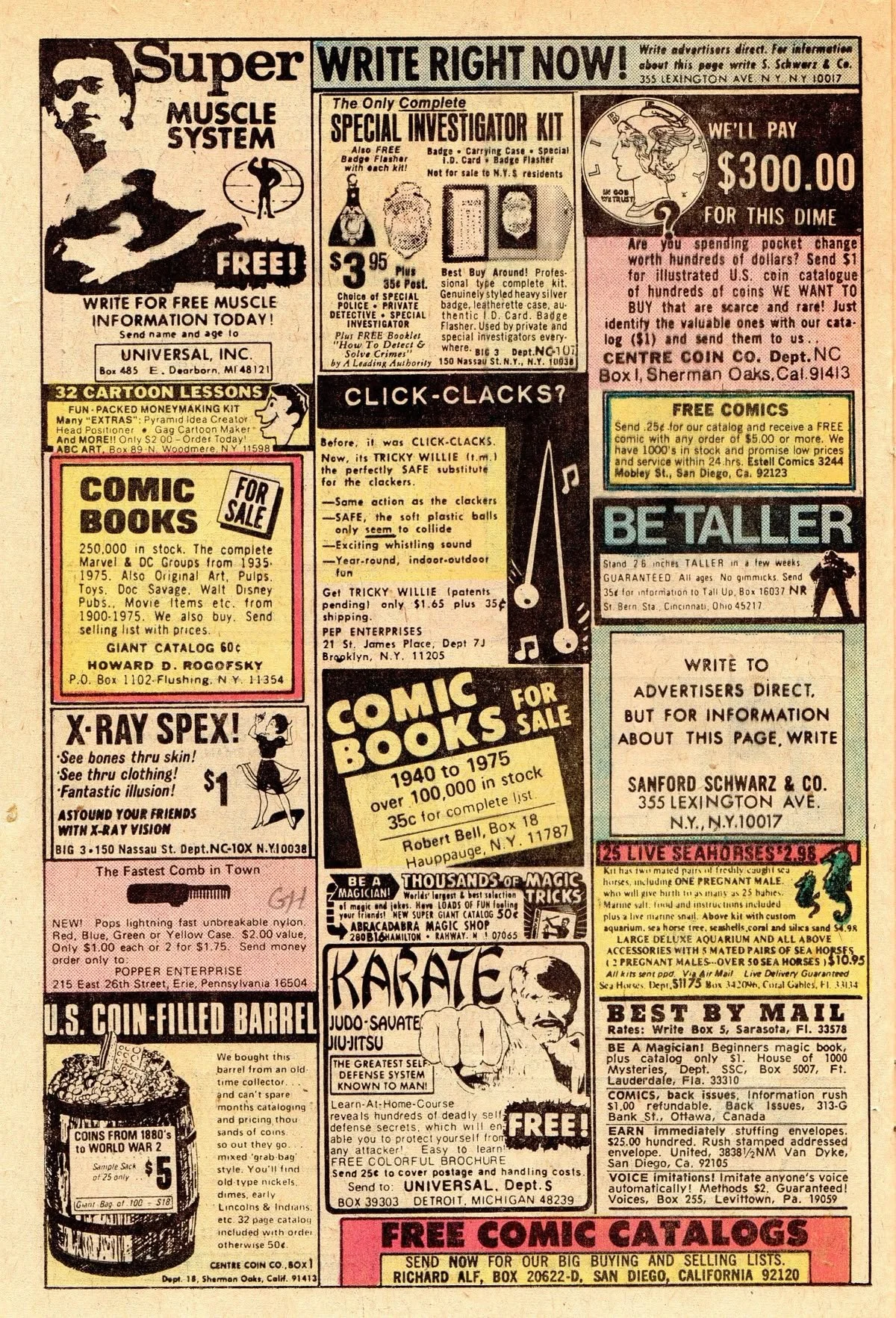

The process started by collecting and analyzing dozens of mid-century comics ads — like Charles Atlas, Sea-Monkeys, and X-Ray Specs — and breaking down their common design components: large headlines, dramatic images, exaggerated assertions, and narrative tension.These aesthetics served as the foundation for a new work, which not only extols and lampooned the original material but also sought to meet halfway between then and now. By way of studies, digital exploration, and compositional sketches, each recreated advert was made to evoke the loveliness of its day while unlocking the persuasive mechanisms hidden within.

Early mood boards combined archival scans of antique adverts with modern advertising visual motifs and highlighted the shared vocabulary of print ephemera and digital adverts. Typography choices were motivated by offset printing texture and pulp-era fonts, and color schemes captured the cheap comic ink over-saturation. It wasn't done as some kind of nostalgic exercise for its own sake, but to expose the continuity between yesterday's fantasy and today's consumer culture.

Each step of the process — from drawing to digital picture — was a matter of semiotic reconstruction: taking symbols of change, curiosity, and power and placing them in critical context. Design decisions were guided by Barthes and McLuhan's work on how form, medium, and message become entwined in order to create belief. Through a reinterpretation of the classic ads in contemporary language, the exercise demonstrated how quickly the persuasion techniques become adaptable to new technology and new viewership.

Section 4

Reimagining the Comic Book Ad Myths

The Final Body of Work takes research into visual form — three reimagined advertisements that revisit such ubiquitous comic book fantasies through a critical gaze.

Each piece imitates the advertising language of mid-century but reveals the rhetoric of persuasion and myth-making that have been addressed throughout the thesis.

These works are both homage and critique, demonstrating how fantasy, want, and consumer identity were constructed in image and text.

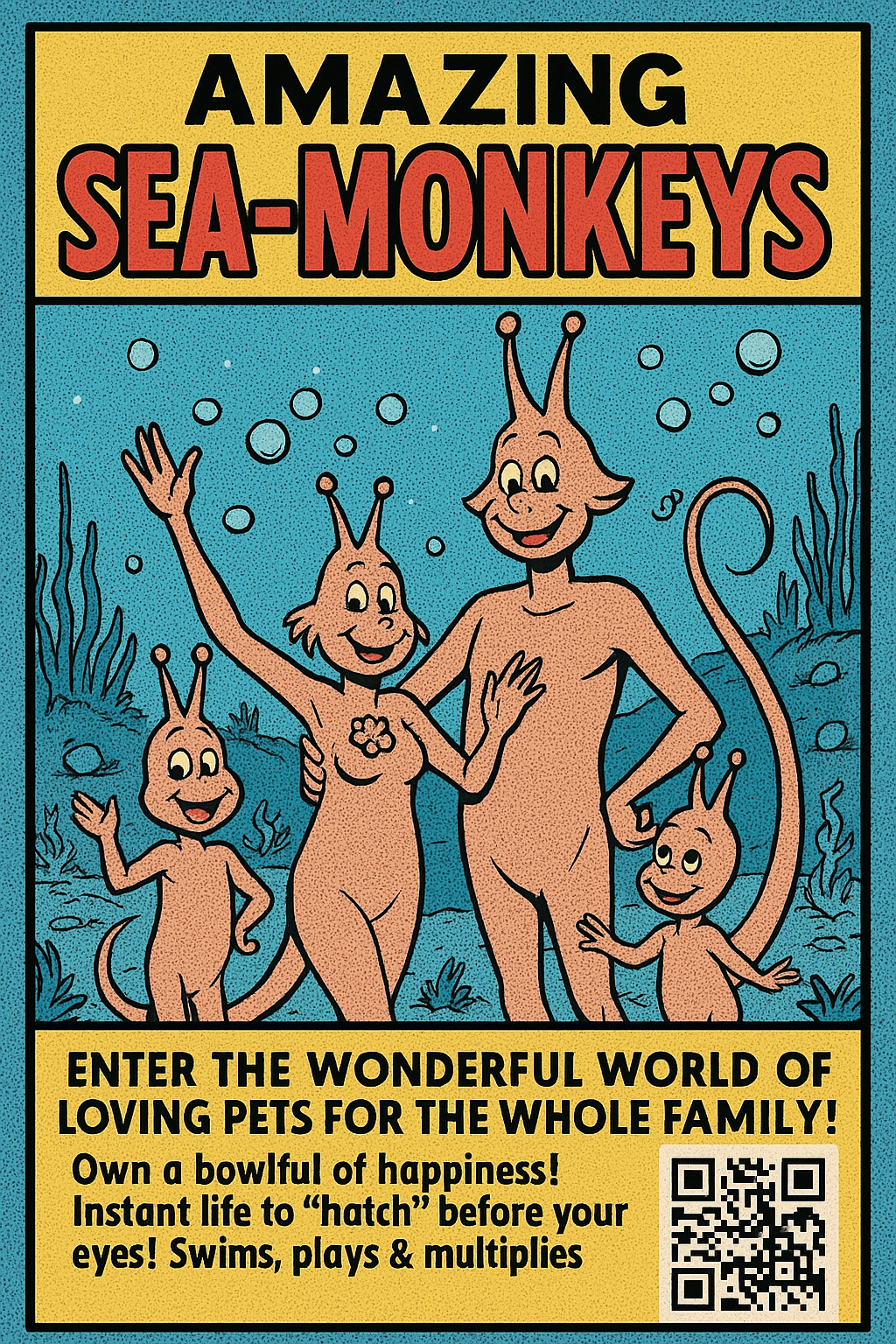

2. "AMAZING SEA-MONKEYS" — The Manufactured Dream

This reproduction of the iconic Sea-Monkeys ad exposes the fantasy of ownership and control that underwrote the original. The grinning "instant family" of critters, once portrayed as a fun-loving pals, gets a makeover as a critique of designed happiness and consumer wonder.

Textures and surreal coloring emulate 1960s printing defects, gesturing toward how fantasy was both sold and homogenized by style.

Design Commentary:

The otherworldly color palette and wondrous drawing conceal an underlying unease — the promise of a living miracle converted into mail-order scam.

In their parody of the ad's over-the-top artificial sheen, the piece itself reflects the transition from innocent curiosity to commercial deception, reminding us how belief was—and still is—constructed through appearances.

1. "#GROWUPFAST" — The Charles Atlas Legacy

This photograph reimagers the classic 97-Pound Weakling ad that promised transformation on the strength of muscularity. The original message—coying weakness to peddle empowerment—is recreated using modern typographic and symbolic devices. Here, the tale becomes an essay on masculinity as performance and the imperative to be better.

The colored figure, gritty condensed type, and jarring contrast evoke pulp-era machismo, while the hashtag structure reconnects the tale with present social media society, wherein affirmation and identity are still based on looks and aspiration.

Design Commentary: The hyperbolic design and narrow color palette capture the illusion of control and transformation that the original ad promised. Blending old form and new iconography, the design shows how ideals of virility are commodified across generations.

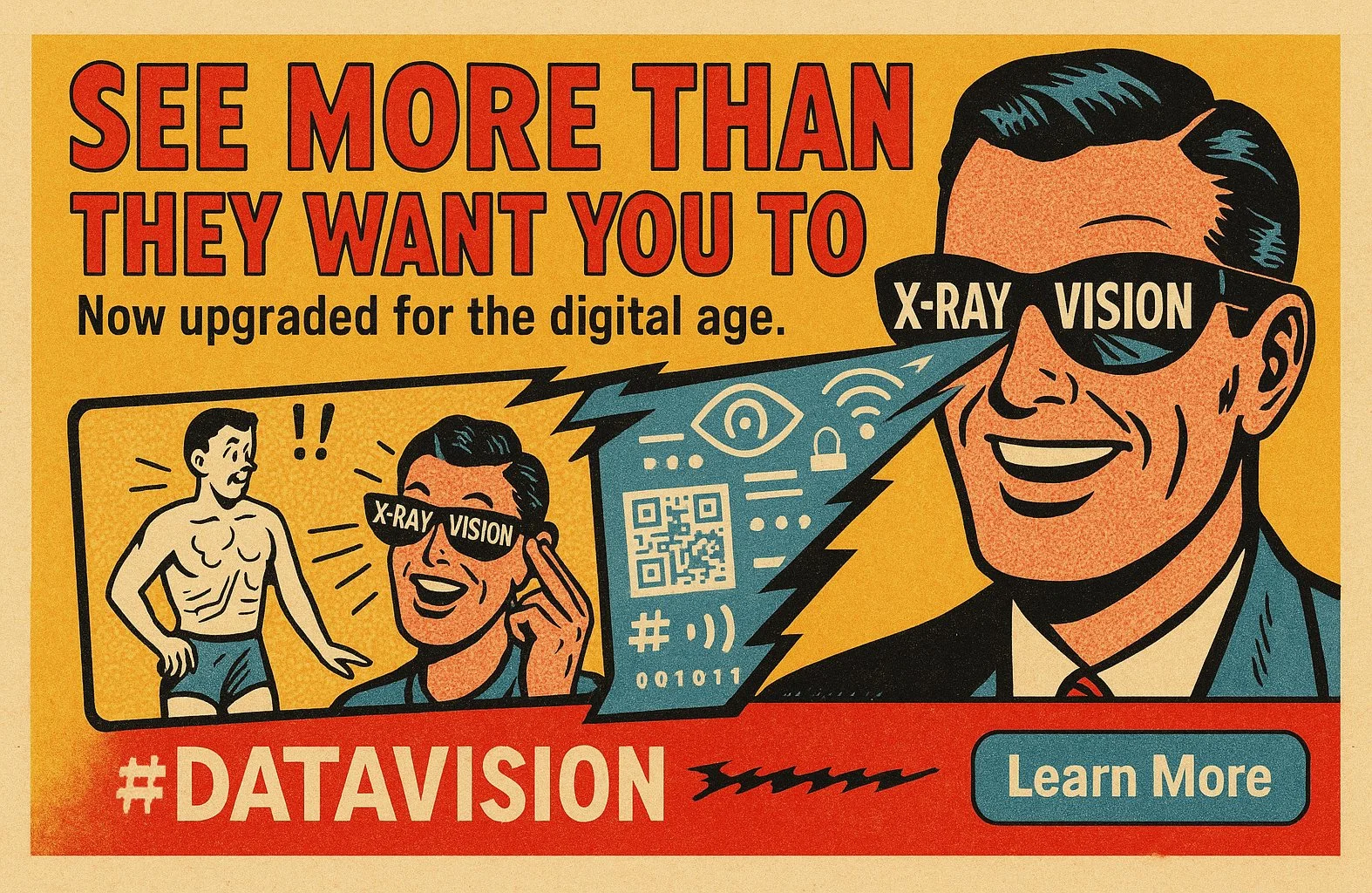

3. "SEE MORE THAN THEY WANT YOU TO" — The X-Ray Specs Paradox

The `X-Ray Specs' ad, once the very epitome of adolescent naughtiness, is updated as a satire of illusion and voyeurism in the media.

The new composition warps the familiar goggle symbol into abstract geometries, suggesting both revelation and concealment.

It invites the spectator to ask not what they see, but what they would like to see—a reflection of how modern advertising plays games with curiosity and desire for illicit knowledge.

Design Commentary:

Created in flat monochrome with superimposed halftones, the work obliterates the line between seeing and imagining.

By making an old-timey novelty toy a metaphor for transparency in the media, the work bridges vintage misinformation to current digital filters and constructed realities.

Reflection

These three reinterpretations, together, create a unifying visual story — one that reframes retro comic book art as a window to the ethics of persuasion.

In appearance, hue, and vocabulary, the series exposes how readily imagination resorts to commerce and the same design strategies remain a part of contemporary visual culture.

Section 5:

Design, Persuasion and Responsibility

This project reexamines comic book advertising not only as nostalgic pop culture, but as a revealing case study in the power and responsibility of visual communication.

Through reinterpretation, each recreated advertisement exposes how persuasion operates beneath the surface — how design can transform emotion into motivation, and fantasy into belief.

The research demonstrates that the strategies once used to sell mail-order novelties—exaggeration, myth-making, and emotional promise—still exist today in digital advertising and influencer culture.

The mediums have evolved, but the mechanics remain: create a sense of lack, offer instant transformation, and reward the viewer with belonging.

As a designer, being presented with this material brings up issues of ethics. How do we balance creativity and honesty? When does inspiration tip over into manipulation? The reinterpretations throughout the project strive to remind designers and viewers both that every image contains intent, and every message changes perception.

From Barthes, we understand meaning is constructed from symbols that can liberate or lie. From McLuhan, we get the idea that the medium itself—comic book, screen, or scroll—is never so. Combined, they challenge us to consider design as something beyond decoration or persuasion, but as a cultural force that can shape behavior and thought.

By returning through these vintage advertisements with a current ethic of critique, Selling the Impossible invites viewers to think through their own relationship to media: to see beyond nostalgia and investigate the systems of belief that design continues to build for us. The work is at once critique and affection—of imagination, of design history, and of the continuing responsibility that attaches to the power of communicating visually.

Acknowledgments

With Gratitude

This book is the result of many years of study, planning, and reflection, and it would not have happened except for the forbearance and encouragement of many individuals.

I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my thesis committee and Liberty University faculty advisors for their continued guidance, critique, and encouragement throughout the process of producing Selling the Impossible. Their professionalism led this work into both an academic examination and creative study of design's cultural impact.

Specific gratitude is given to The Baton Exchange, whose mission and leadership shaped much of the values seen in this effort. Their focus on development and leadership mirrors the very same paradigms of transformation throughout this investigation.

I also owe a special debt of gratitude to my family, friends, and fellow staff members for their patience, encouragement, and faith in my aesthetic vision. Each gave the sort of unobtrusive support that makes possible the extended time involved in making and thinking.

Finally, this project is for everyone who still sees design as something more than visual expression, but as a means of understanding the human experience—a means of analyzing the way images, words, and ideas build the person we are and the person we want to become.